Government policy and services are inextricably linked, and so people who make policy decisions should join up with those who design and deliver services for people.

Let me explain why I think that’s so important…

A policy is a set of prescriptions for what should be done to achieve a goal. For example, the recently published Prisons White Paper is a policy document that describes what the UK’s government wants to achieve and how it plans to do that over the next 2–10 years.

But what is a service, how are services related to policies, and how do both of those matter in the everyday lives of ordinary people?

People interact with services all the time in their day-to-day lives in order to achieve some short-term goal. For example, if I want to visit my friend in prison, I’ll probably search Google to find out how to book a visit. Coming across the GOV.UK page for High Down prison, I’ll discover that I can now book a video call instead, if I want to. If I still want to visit in person, I’ll call the prison phone number and talk to someone to book my visit.

When the day of my visit comes, I might travel to the prison and engage with several different prison officers to check in, see my friend, and check out. Or I’ll use the app I’ve downloaded to access the video call, while my friend will be escorted by a prison officer to a special room in the prison where they will chat with me over a computer.

These are all aspects of a service that have been designed to function in a certain way. I can interact with aspects of that service online, over the phone, and in person. I may or may not pay a fee, or incur other costs to use them. The components of the service are operated by various prison staff. All of that should be thought through and thoroughly tested, to make sure the whole service works and everyone is able to visit someone in prison as easily and cost-effectively as possible. And this service, like all others, is dependent on countless other services to function.

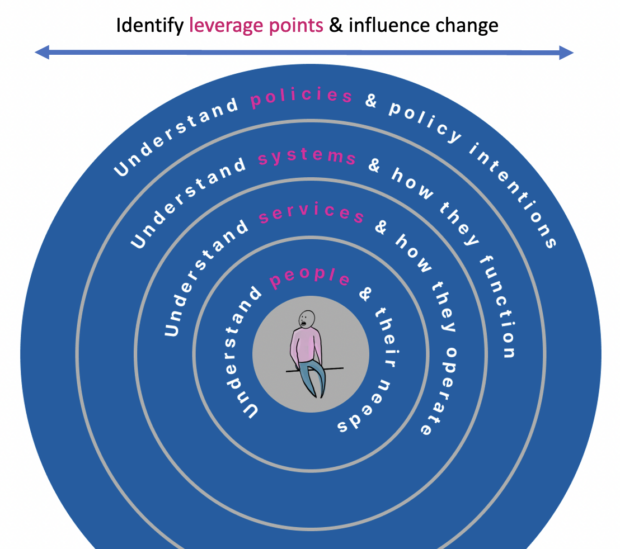

Government policy objectives are achieved when complex and continuously changing networks of people, organisations, and services all function effectively. And so policymakers tasked with achieving certain outcomes for society must understand how services function, and be able to understand how systems of services and individuals and organisations function, if they are going to make meaningful progress toward achieving those objectives. They should work closely with the people who are designing and implementing those services.

Policymakers as stewards of systems

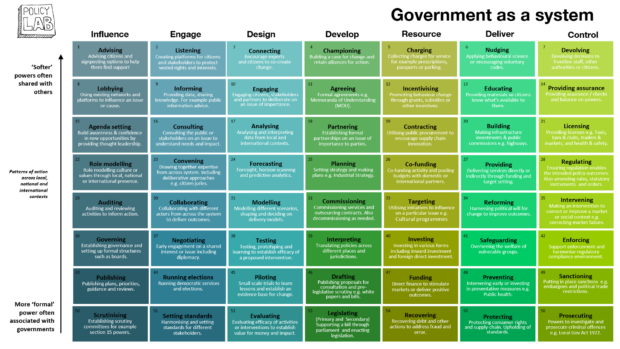

A policymaker’s job is not to design or deliver any individual service that people will use — those jobs are done by all kinds of specialists across and beyond government. The policymaker’s role is to design and oversee the entire ecosystem of services that people engage with to achieve the objectives government sets.

This is important because a system steward will think longer-term than a specific problem-solver would. They will aim to create changes that make the system healthier over time. That might include thinking about system dynamics, network thinking, self-organisation, emergence, and game theory, or leverage points and the different places to intervene in a system.

Above all, they will look for opportunities to make changes that are longer-lasting, that improve the overall health of the whole system, that outlive their own brief roles in the system.

Policymakers need to get out of the building

Reality is very different from our assumptions. The only way to understand what people want and how they will interact with services is to ask them — and ideally to test out aspects of those services in real-world situations.

A colleague of mine is working on an idea for a service that would streamline activities and appointments that people leaving prison must attend in the days just before and after they’re released. After dozens of interviews with people in prison, people who had left prison, and people who work in the detainment and rehabilitation system, a conversation with a peer mentor in prison led her to completely rethink what was possible and how the service could work. You never know when those lightbulb moments will come, or what will spark them.

Effective teams are regularly talking to people who will use and deliver the services relevant to the systems they’re trying to improve. They’re asking ‘why’ — why things work this way, why they don’t work that way. And they’re thinking about ‘how’ — how might we do things differently? How might we do things better?

In digital service development it is said that every person on a team should be engaging with people involved in their service for a bare minimum of 2 hours every 6 weeks.

In fact, there’s a whole set of professions that know how to design and deliver services together with the people who use those services — these are the service designers, user researchers, content designers, product managers, delivery managers, and others who tend to work in digital teams in government.

Multidisciplinary teams to join-up policy and delivery

In the Ministry of Justice, our User-Centred Policy Design teams aimed to join up those service design specialists with policymakers. Our service-design teams often acted like an internal consultancy, agreeing a problem statement and project brief with a policy team, then conducting the research and design activities needed to better understand how to improve the situation, and returning with a series of insights and recommendations. That is powerful, valuable work that helps policymakers better understand the problem spaces they’re working in, and make better decisions about how to improve things.

It’s even more powerful when the policymakers engage directly with our teams, observing research activities, synthesising insights, designing improvement ideas, talking to ordinary people and justice system staff about how those ideas might function in the real world. That level of engagement enables us to build in their perspectives, often around the feasibility or viability of an idea, into our recommendations for how to improve the system. And it gives policymakers a much more realistic understanding of the services and systems people engage with.

In the cross-government Prison Leavers project, we have embedded service designers and user researchers and delivery managers in teams with policymakers. Our teams are called ‘service communities’, but they’re focused across the whole system, not any single service.

It’s a powerful combination, transforming our approach to policymaking to be more agile, person-centred, and community-centred. Our service community teams are thinking about how they can steward the whole system to provide better outcomes for people leaving prison and for society as a whole. They know they need to work not just across central government agencies but also with the health sector, local government authorities, accommodation providers, social enterprises, local businesses, community groups, and more… because none of these institutions can achieve their goals alone, and government can’t achieve its goals without all of them.

These multidisciplinary teams have the skills to see and improve the whole system (policy design), while also identifying and improving various parts of the system (service design). If they’re constantly working to improve specific parts of the system, while keeping an eye on how the overall system reacts and evolves after each new change, we’ll slowly but surely improve the state of our national detention and rehabilitation system. We’re still at the early stages of this work, but this feels to me like what ‘policy design’ should look like.

Our service community teams are focusing on people, services, systems, and policies to influence long-term positive change.

Join our community

We use this blog to talk about the work of the multidisciplinary policy design community. We share stories about our work, the thinking behind it and what policymaking might look like in the future. If you would like to read more, then please sign-up for blog updates in the sidebar of this page. If you work for the UK's government, then you can you join the policy design community. If you don't work for the UK government, then join our AHRC Design and Policy Network.

2 comments

Comment by john mortimer posted on

A really insightful and helpful post. Much to think about; taking policy closer to citizens, collaborative working, and multi-discipline. Helping to expand and link Digital and Change

Comment by Marc posted on

Thanks for sharing your experiences and thoughts. It resonates very much with thoughts I had, on how design practices are simultaneously constrained and enabled by both the material and the discursive practices of the collective. In the experience you share, it seems that your multidisciplinary teams are successful as they question and re-shape simultaneously the policies (discourses shaping a problem in a particular, fair, and legitimate lens, and shaping at the same to limited ways to create the service) and the services (capabilities enabling one to act). I recall Foucault's explanation that a prison is a historical 'relationship' between a discourse (at his time on "delinquency") and a material structure (the "correctional" complex). In your approach, it seems that you create the possibility to collectively acknowledge this given relationship of matter and discourse, and therefore open the ability to act differently, create different futures.