In 2020, a user-centred design team at Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) was given a mission to create a service map.

Whereas a service blueprint sets out all the interactions that constitute one service, a service map presents a number of services that somehow relate to each other, perhaps involving the same user, delivery bodies or policymakers. How you present that information is up to you.

DLUHC is a small policy department, so we started from quite a different place than previous work other departments have done to create service maps or lists. The challenges went beyond finding and mapping services, and through a series of three blogs we want to share some of our learning with teams who may be looking to start something like this from a similar position. We’ll be sharing reflections on how we went about designing the service map artefact and the multifaceted value it could bring to public policymaking in different departments later in the series.

This first post explores our initial reaction to the challenge of being asked to make a service map for our policy department, DLUHC. It covers where we began, who we had in the team and how we grappled with some of the big questions that emerged from our attempt at thinking about services and policy together.

Taking a service approach for the first time

In October 2020 DLUHC (at that time Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government) was coming out of the first phase of COVID-19 response. COVID-19 had created a lot of new work, so the department’s management constantly had to prioritise members of staff and pieces of work to make sure the right outcomes were achieved. I use “pieces of work” deliberately – because it’s a catch-all term that can cover lots of things, especially in a policy department. Work is often assigned shorthand labels such as “shielding programme” or “business support grant”, but these things could involve a multitude of activities, costs, contracts, research, legislation and so on. It’s hard to make sensible and rapid prioritisation decisions if you don’t know exactly what needs to be done.

The department's work on COVID-19 stretched beyond its typical policy stewardship role and into more operational service delivery, and senior leaders had reflected on the need for different skills and approaches to reflect this changing role. The Chief Digital Officer wanted to support this shift and use it as an opportunity to broaden the department's perspective beyond its traditional policy framing. After all, the department had been responsible for considerable nationwide delivery for years (for example, in regeneration funding) and there was an opportunity to improve the quality of that work by using a service perspective to better connect policy work with the real-world user impact of these decisions - a shift in thinking that has been emerging from digital and policy teams across government through groups like Policy Lab and OneTeamGovernment. There was also an opportunity to use service thinking to identify reusable components or approaches that lay horizontally across a department that remain primarily organised by policy areas.

A user-centred service approach is quite well established in the more operational government departments, following many years of development of the concept and best-practice delivery of government services, led by Government Digital Serivce. Those departments understand that the government is providing a service every time it offers people a way to do something, like get a driving licence, qualify in a profession or access an entitlement. Services need to stay ‘switched on’ and they must work well during their lifetime, so that people can get what they need, when they need it. There is a cost to providing every service, even if it’s just a little bit of staff time, which should be weighed against the service’s benefit to the public. We knew that we could make better resourcing and prioritisation decisions in DLUHC, if we could identify which “pieces of work” were services that needed to be treated in this way.

Enter the team

That’s where we came in. The team began with one Product Manager, one Service Designer and an extra pair of hands from our digital team, then expanded to include a Content Designer and a User Researcher. In our initial roadmap, we envisaged a discovery phase looking at the problem space, an alpha phase prototyping a product to meet user needs, and an assessment of how to continue into a beta phase.

We started off by looking at other service maps that existed across government: from the Home Office, the Department for Education (DfE), and the Ministry of Justice. DfE felt the most similar to our own department in terms of a focus on policy. At this stage we weren’t even sure how to define “service” for our service map. Was briefing ministers a service? Was our commercial team providing a service? What if the market played a role in the service? One of the things we learned from other departments was to start with was the user – to conceptualise each service in terms of what it enabled someone outside the Civil Service to do. Following this logic and to limit our scope, we ruled out internal services, as they felt like a different category of business activity.

Where policy meets delivery

In traditional policymaking, policy is seen as separate to implementation (also known as delivery). However, recent best practice in policymaking emphasises the critical link between the theory of a policy and the reality of how it is delivered. From a user’s point of view it doesn’t really matter who is doing the delivery.

As a policy department we didn’t use ‘services’ as a day-to-day way to organise our work and it wasn’t straightforward to gather a simple list. We used all the sources we could get our hands on to find as many of DLUHC’s services as we could: the business plan, our intranet, Contracts Finder, GOV.UK service lists, even Hansard!

We used the metaphor of orbits to try and clarify our understanding of how near to DLUHC a service was. It 'felt like' bin collection wasn’t as core to the department as giving out local growth funding…but why? We had lots of debates about ‘responsibility’, ‘lines of accountability’ and ‘outsourcing’. A service may still be crucial even if it isn’t a political priority, or if only 1 person works on it, or if it’s been around for ages, or if it’s actually delivered by someone else. We agreed that if a service landscape could be traced back to a policy originating from the department then it was only right that the department was considered responsible for whether it was achieving the policy outcome (or not).

As a result, we drew a few more lines: we ruled out services that were run exclusively by local government (like bin collection), but we ruled in services that were delivered through DLUHC’s Arm’s-Length-Bodies.

Putting it all together

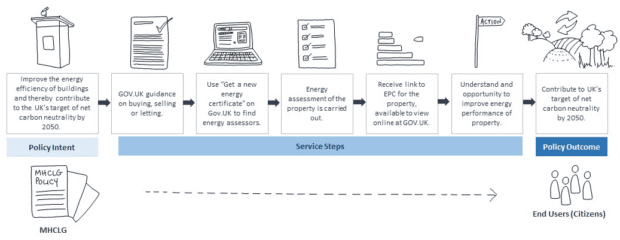

We’d found all these different services DLUHC was responsible for, but the challenge of communicating the link between them and our policies to senior stakeholders remained. We developed a diagram to help. In it, you may recognise the ‘theory of change’ principle that good policymakers use. But we have also included the detail of operational delivery to illustrate our belief that designing services that work for users is the key to creating interventions that demonstrably achieve policy outcomes. This helped us to start the conversation with senior stakeholders and colleagues across delivery, policy and change teams; framing the work we do in the department through a service lens.

Because policy-making brings an additional ‘internal’ layer of actors, considerations and outcomes to the ‘external’ or ‘real-world’ things that happen as a result of policy, it was really hard to try and apply service thinking in the traditional policy landscape. However, once we managed to conceptualise this split, it was hard to remember a time when we couldn’t see it. That’s why we wanted to share what we found and we’d love you to get in contact if this is something you’re trying to do too.

In our next blog posts you can read about the service map artefact and how we made it, as well as the value it could bring to your organisation.

Join our community

We use this blog to talk about the work of the multidisciplinary policy design community. We share stories about our work, the thinking behind it and what policymaking might look like in the future. If you would like to read more, then please sign-up for updates.

Leave a comment