Have you ever felt frustrated when using a service? Rolled your eyes after trying to do something online, having to phone up and hearing the message telling you to look online? Got that sinking feeling when you’ve filled out every box but the continue button is still greyed out? Suddenly realised it’s going to take longer than you thought, when you’ve typed the whole problem out but the chatbot says “sorry, I can’t help with that”? Even though there are lots of services out there with smooth user journeys and great customer experience, a common part of daily life is navigating through services that seem to put obstacles between you and the thing that you need.

Bad service design can do much more damage than making us annoyed. I recently helped an elderly person who had got locked out of their phone. There was a time constraint and extra pressure: they were just about to catch a Eurostar train, but had lost access to their e-tickets. The situation caused the person to go into an anxiety spiral. They were beating themselves up, repeating “I’m so stupid”. The level of distress caused by this mistake might seem silly to you, but it was genuinely felt by that person.

Public service design should do no harm

There is a feedback loop between a person’s emotional state and the person or thing they are reacting to. The feelings sparked by the original event or the design of the thing affect how the person behaves next. In this case, the person’s distress caused them to mix up their passwords, making the problem worse. The design of the recovery process was insufficient to calm them down or direct them to a simple resolution, so things continued to spiral. That design could be characterised as an active factor in that person’s distress.

Not only does design have a significant impact upon the happiness of the people who interact with it, it also significantly contributes to the likelihood that the desired outcome will materialise. In the world of commerce this is well understood, with designers fine-tuning websites, products and offers (and emotional experiences) so that customers conclude that the benefits of buying the product will outweigh the cost.

In the public sector, design is arguably far more important and far less well understood. Why? Monopoly power. Where there is no choice of provider, the design of the only permitted pathway is critical, but there is no incentive to make it great. After all, everyone has to use the thing whether they like it or not. Unless the people designing public services spend time with their users (and non-users), the monopoly means they only infrequently glimpse the behaviours that result from poor designing: avoidance, denial, inaccurate information, false declarations and failure demand. If users do end up managing to successfully complete the transaction, their irritation, confusion, shame and distress along the way is invisible.

Public services should expressly drive the outcomes they aim to achieve, and they should ‘do no harm’ to the citizens they aim to serve. That’s uncontroversial. So why are we not systematically using the discipline of design to minimise individual distress and the counterproductive behaviours that flow from it?

Designing against distress

There has been a lot of work done in recent years on designing for accessibility, with leading organisations emphasising how good design can help people navigate services in particular circumstances from using assistive technologies to looking at a screen in a sunny park. I want to propose a similar approach to designing to prevent distress. I’ve chosen this term because it is widely understood to cover a range of experiences from trauma to light upset.

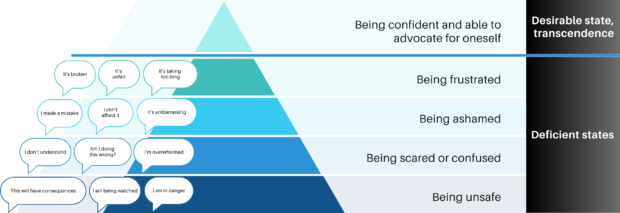

Reflecting on my example of an elderly person’s experience of becoming distressed by a bad user experience, I started thinking about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. You may recognise the pyramid, which offers a model for how people react to situations. If people are hungry, they can’t think about anything except their hunger. This spills over into their behaviour: they might steal food to satisfy that hunger. The need is overriding things that would, if it wasn’t for the need, be considered very important, like morality or honesty.

Maslow used a pyramid structure to illustrate the hierarchy: at the bottom are the needs that, if unmet, have the most detrimental impact. The top of the pyramid shows the desirable state where none of the basic needs are lacking. Since its conception, this model has helped people understand the drivers of behaviour in the context of what an individual is experiencing.

I propose a hierarchy of emotional needs in relation to services. Unlike Maslow’s needs, which apply to an individual in a particular situation, these needs specifically relate to an interaction/ transaction that an individual is experiencing with another party such as a private company, public servant or other service provider.

My model identifies four deficient states. The state at the top of the pyramid cannot be reached if any of the deficiencies exist. Each deficiency has an emotional impact, in that the person’s wellbeing is reduced. It also causes a behavioural impact that has consequences for the individual, anyone they might be interacting with and the desired outcome of the interaction. The model ranks the states by the ‘average’ emotional impact, from least to most harmful. However, this is a generalisation. People experience setbacks differently, and they react differently. Importantly, the behaviours that stem from the different types of distress might be the same – for example, both a person who is frustrated and a person who is scared might completely disengage from the interaction. In all these deficient states, the service is not serving the person: it’s actually harming them

Perhaps it feels like common sense that services are designed in relation to the state that the average user is in when they first access the service, particularly if it’s a question of a difficult life event. By and large that’s true. Emergency call handlers are trained in how to guide people through unsafe situations. Volunteers for helplines know that their callers are likely to be distressed. However, it is often the case that after that ‘front door’, the service stops reducing or preventing distress, and in some cases adds new burdens and trauma, which has consequences for how people behave as they move through that journey.

Any element of an interaction or service can create new distress. As I have tried to show with my examples, distress can develop in response to issues as varied as technologies, wording, decisions, bad wifi, lack of information, risk assessment or user error. It can also develop in relation to the whole experience: people grow weary and cynical if time passes, they keep pushing, but there is no resolution. Service design is critically important precisely because it is the only discipline that encompasses all of these and the feelings of the individual users.

Design is the backdrop to significant life events

When the stakes are very high, users need to be able to make good decisions, but they are also more likely to be stressed. Claiming asylum, divorce, medical diagnoses, accusations of crime, large financial transactions: these are the situations in which people most need to be able to effectively navigate services to get the right outcome for them. The services are not a neutral portal – they are the experience: best when they guide, defuse and resolve, worst when they cause additional shame, pain or fear.

The poorer the design of a service is, the more important it is that the person who is navigating it be focused and clear-headed. We instinctively embody this when we sit down, turn off the tv and concentrate on putting the right combination of flights and luggage – but no extra hire cars or insurance policies - into our shopping basket. When design is unintentionally or intentionally poor, it is the user who has to make the effort to get it right.

Sometimes, individuals experience a perfect storm of these factors. They are in a high-stress situation, the outcome of which will be critical to their future. However, they are facing a complex, poorly-designed service that can only be navigated by people who are articulate, patient, confident or even pushy. Sound familiar? This is often the case for services provided by the courts, police, border control, the NHS and central government.

Ironically, these services only exist to cater for people in some sort of distress; in many cases the user will be vulnerable by definition. That is completely different from a consumer’s free choice to buy from a budget airline’s dodgy website. Individuals are compelled to use the designs public servants make – unless they’re so emotionally impacted that they go down a ‘bad path’: non-compliance with a law, evasion of responsibilities, or disengagement from the structures society has put in place to supposedly help them.

Design can prevent and remedy distressing experiences

At a basic level, we have an ethical responsibility to stop adding to people’s distress. In addition, we need to employ design to prevent behaviours that sabotage the outcome we are aiming for. The discipline of design has so much to offer the public sector, from the minutiae of service interactions in specific situations to the overall feeling that our democratic institutions are creating the sort of society people want to live in. Every public servant has this power – the power to design well, eliminate distress and make a positive difference to the people we are here to serve. What can you do to design danger, fear, shame and frustration out of people’s experiences?

Join our community

We use this blog to talk about the work of the multidisciplinary policy design community. We share stories about our work, the thinking behind it and what policymaking might look like in the future. If you would like to read more, then please subscribe to this blog. If you work for the UK's government, then you can you join the policy design community. If you don't work for the UK government, then join our AHRC Design and Policy Network.

4 comments

Comment by john mortimer posted on

This is common in the public sector, and a very important topic. I have lost count of the problems that ill-designed accessibility creates. The top ones in local gov are universal credit, and then housing.

When people are in trouble, they need help, support, and might be in some sort of crisis. Their needs are not single service needs, they are almost always complex and varied. The primary way to understand this complexity is enquiry - listening to them. Understanding them and their wider context.

Thanks for raising this.

Comment by Alice posted on

Thanks for commenting John. Listening empathetically comes up time and time again in public services but that need isn't always met in a digital channel. I wonder if it ever can be?

Comment by Ben Sprung posted on

Really interesting article. I have thought about this a lot recently as a result of research on a project I have worked on and person experience. Perhaps an additional challenge for design in this space is that people in distress often have to interact with multiple governmental and no governmental services to achieve their goal?

Probate is one example of this, I discovered when conducting user research on Home buying and selling. What could me more stressful than dealing with the death of a loved one?

Another example is Bona Vacantia, when a businesses closes and they do not take funds out of the bank resulting in the account being closed and the money going to the government's treasurer. You have to apply to the court to get permission to reopen the company to claim your money. Users have to interact with the courts, the Government's and Companies House. Every step is fundamentally broken.

Both of these are high stress times made much worse by a lack of end to end thinking and design.

Comment by Alice posted on

Hi Ben! Absolutely agree with you, especially on multiple services. I am increasingly interested in the frustration and distress caused by having to repeat your story/ your details. It was a theme that always came up in my MoJ days. It's something about reliving trauma - not just the fact of having to spend time re-telling.