My customer experience team was challenged by ministers to build a ‘Tube Map’ for young people to track their aspirations and qualifications to help them get to their intended career destination. And on the face of it, this sounds like a great idea …fun to use and engaging.

Our worry though was that no customer research had taken place, and no one had checked its technical feasibility. Instead of pushing back on the idea, we chose to approach it using design thinking, saying “Yes, and…”

The best and quickest way to tackle this type of problem is to run a design sprint: to take the idea, and the problem it aims to fix, and to rapidly build, test and iterate around it.

Design sprints focus on what is needed

We built a multidisciplinary team of policy and delivery professionals from across the Department for Education, plus minister’s special advisers and external frontline experts like careers advisors.

As their design sprint unfolded, the team found that ideas other than the ‘Tube Map’ might also be valuable.

Testing these ideas with customers really helped get clarity on what works and what doesn’t work - with zero sugarcoating.

The ministerial team’s original assumption that young people would love a clear path mapping their future was true, but the reality is that sixteen-year-olds think that 5-years is an eternity into the future. What they really want is to see a range of possibilities, not a single destination on a tube map.

Whilst the result of this design sprint didn’t validate the original solution, it helped us avoid spending public money on something that wasn’t needed. That, in turn, enabled us to divert that investment to other important education improvements that students say they do need, and provide ministers with a portfolio of successfully delivered initiatives.

This small design sprint sparked 3 major digital projects and the creation of a careers website that shares all the possible post-school options for different qualifications in England.

So what exactly is a design sprint?

Innovation and creativity are widely used terms across all levels of government. However, neither happens in isolation or as a one-off light bulb moment.

All of the great inventions of modern times have come from numerous failed attempts and trials. Even the aforementioned light bulb took Edison 10,000 failed attempts before finally illuminating his work.

A design sprint is a process for rapidly prototyping solutions to difficult problems. It helps teams to create new products and services or to improve existing ones. Originally defined by Jake Knapp (formerly of Google). He honed the process over time, publishing multiple books and sharing some great video content that I would highly recommend viewing.

A design sprint compresses months of potential work into an intense week. This is very helpful for government design teams. It allows us to glimpse the future, without the time or the expense of building a complete and finished solution.

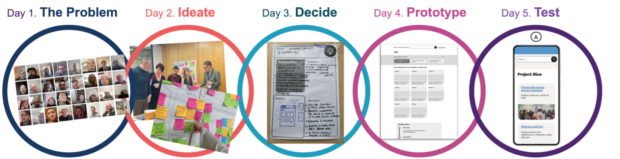

Design in 5 days

My team has developed its own version of the design sprint. I’ve described a full 5-day version of it below - but 5-days out of anyone’s calendar is a huge ask. We’ve also tried 3-day sprints which can work for smaller defined problems, but this often leaves more questions than answers - although this can be valuable to help kick off a larger project. Another approach is to split-up the days across a couple of weeks. This can be positive as it gives teams time to reflect, if you can keep up the momentum and focus.

Day 1: Understand the problem

The first day is used to examine the problem. This is not a day sat in an isolated room or online. We bring in experts to share their research and findings so we can understand the wider context. We visit and speak to real customers so we can get their take on issues and really understand their needs. We park our assumption of what we think will work, and we review the work of others outside of our organisation. This is a day to soak-up information and be inspired by customers and those who have previously worked in the space.

Day 2: Ideate

Day two sees us release the handbrake and create as many ideas as possible. There are a number of techniques for ideation (such as Crazy 8’s) that are great for generating a vast quantity of ideas.

Asking people to “ideate” can be very intimidating. Often the ‘fear-of-the-blank-page’ needing to be filled with amazing ideas is quite overwhelming. We instead begin the day with negative innovation and ask ‘What’s the worst thing we could do for customers? How bad could we make the situation?’

Once this session is over, ideation is simple. Just ask the group to do the opposite of their bad ideas to fix the problem and meet the needs of the customer.

Day 3: Decide

At this stage, we should have multiple great ideas that we hope will change the world for the better. But we can’t test them all, so we need to prioritise our efforts.

One of the most difficult parts of the process can be to let go of our ideas. No matter how much we try to be unbiased, we all naturally think our ideas should be ‘the one’.

There are many ways to narrow the options, such as democratically voting with dots on each sketched idea.

One technique we found works well is Break it, Fix it. We ask the team to get into three groups and pass their own ideas onto others. We then ask the groups to purposefully break the ideas and show why these won’t work. The next step is to pass the ideas on again to another group to allow them to fix and iterate upon the ideas. This process allows us to let go of our precious ideas and trust the rest of the group with them, to break and fix. More importantly, it allows everyone to interrogate each idea and really look at its viability. Often after this exercise we find the team has already come to a consensus as to which ideas should be taken forward, without the need to vote on multiple options.

Day 4: Prototype

The fourth day is for building a prototype of the ideas they wish to test.

We remind the team that this is not about making a perfect version. Instead a prototype should be rough, it should need further polish.

The roughness of a prototype is its secret power. If you share a shiny perfected product/service with a potential customer for testing, then they are unlikely to criticise it because they can see how much effort has already gone into it.

If you instead share a cardboard prototype held together with sticky tape and say it’s been put together in a day, then they are far more likely to be honest and unworried about hurt feelings or wasted money.

Day 5: Validate

It is time for the team to move out of the safety of the office and go speak to potential customers. It’s the time to share your big idea and show how it will change lives for the better.

This is such a valuable day as the team listen and see how customers react to their idea. It’s on this day that you may find all your ideas are brilliant or off-the-mark (which is hugely insightful as well).

The benefits are clear to us

Yes, design sprints are a lot of work. It’s intense, and it can be like herding cats, trying to get people together and potential customers in place for testing …but it is worth it.

Confirmation that your ideas work, helps you build an investment case. But it is equally as important to know which of your ideas don’t work.

Knowing you’ve failed in 5-days rather than in 6-months means you can move forward much quicker with only a tiny amount of resource used. Alongside this with each failure brings an enormous amount of valuable feedback from customers that no one else has discovered until this point.

If you can build a team of policy professionals alongside those in delivery (like designers, developers, research, subject matter experts) and customers, then the whole process is invaluable.

We’ve had heads of policy and directors seeing first-hand why their prior assumptions won’t work. Plus they’ve been a part of developing a new solution that tested well with customers. From that point onwards the solution has near-perfect support and buy-in from senior stakeholders.

My advice to anyone is to always sprint before you walk!

Join our community

We use this blog to talk about the work of the multidisciplinary policy design community. We share stories about our work, the thinking behind it and what policymaking might look like in the future. If you would like to read more, then please subscribe to this blog. If you work for the UK's government, then you can you join the policy design community. If you don't work for the UK government, then connect with us on social media at Design and Policy Network and subscribe here to be notified about our monthly speaker events to hear from influential design thought leaders and practitioners.

1 comment

Comment by Lisa Jeffery posted on

Great blog post. Thanks, Mark and team. A really useful example of ‘learning by doing’. It’s so important that we do not become too attached to our ideas before they are proven.

A couple more links to other examples for anyone wanting to explore this format:

https://designnotes.blog.gov.uk/2020/01/10/what-its-like-to-run-a-gov-design-jam/

https://digitalpublicservices.gov.wales/blog/exciting-milestone-first-leading-modern-public-services-cohort-graduate