Most of the insufficiencies of government can be traced back to a fundamental misunderstanding about how to ‘solve’ the problems society faces.

As humans, we seem to be hard-wired to see the world in terms of discrete problems we can solve. Our brains are always breaking things down to their component parts, looking for ways to fix them. We are constantly seeking greater and greater simplicity.

And that works for math problems, or engineering problems. You solve the component parts of the problem — no matter how many there are — until the whole fits together perfectly. We can do that to make a concrete block, or to build a wall from those blocks, or to build a prison from those walls.

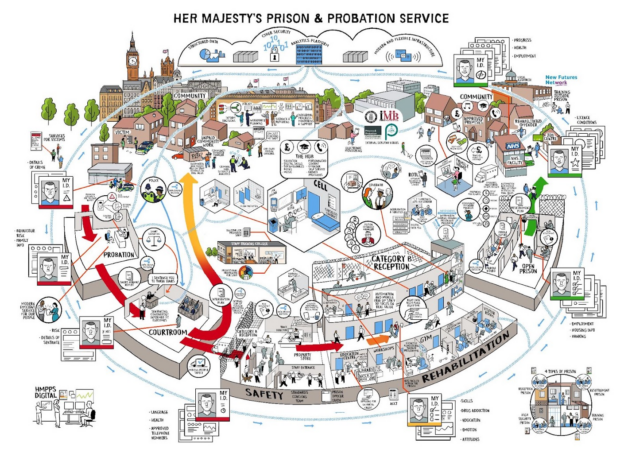

But building a prison system that keeps people safe and creates a healthier society — that is another matter. It’s not simply a question of compiling all the right parts and assembling them in the right way. A prison system — one that ensures safety and promotes rehabilitation — has an infinite number of component elements, all of which are interrelated and continuously changing, often in unpredictable ways. That is what we call a ‘complex’ (or ‘wicked’) problem.

The vast majority of problems government addresses are these kinds of ‘complex’ problems. How to reduce crime. How to educate our children. How to increase prosperity and keep people healthy. There is no one right answer to these problems — there are just better or worse situations we find ourselves in.

Complexity theory tells us that the way to tackle complex problems is completely different from how we tackle discrete problems with a finite number of variables. For those kinds of problems — even the most complicated ones — we bring in the experts and let them analyse the situation and draw up a blueprint for how to best fix it. Think of a skyscraper — you hire an architect to map out exactly how everything will fit together, and then building engineers with expertise in each step of the process. But in that case, you are able to map out exactly what the end solution will look like from the beginning. The ground is not shifting beneath you.

In complex situations, however, there are no tried and tested answers and everything keeps changing. This is what architect Ann Pendleton-Jullian and scientist John Seely Brown call living “in a white-water world”. We must tackle those challenges differently, through a process of probing, sensing how things change, and reacting to those changes — in other words, a process of quick, continuous, and never-ending experimentation. You want to reduce crime and make communities safer in this particular society at this particular moment in its cultural, economic, and political history… you want to educate young people more effectively, improve people’s health, make work more rewarding… there is no blueprint for any of these, the ‘answers’ will only be found through continuous rapid experimentation.

And I put ‘answers’ in quotation marks because we must get comfortable with uncertainty. In fact, there are no right or wrong answers — in complex situations we are constantly operating in uncertain waters. But what we can do is stubbornly work to improve things, incrementally and continuously, by experimenting with approaches that are safe to fail but designed to teach us what can work at that moment, in those circumstances.

Business consultants David Snowden and Mary Boone say that in situations of flux and unpredictability, where there are no right answers, many unknown unknowns, and many competing ideas, the only useful approach is to experiment in ways that probe the system, then sense changes in the environment and respond proactively to those changes.

Unfortunately, I think we’re currently taking the wrong approach to solving most of the issues we’re faced with. We rely on experts even when there’s no blueprint they could possibly create for us — they do their best, but the domain of uncertainty is not the domain of experts.

We’re using a hammer to bang in a screw, and we don’t understand why it won’t stay in.

Complex problems will never be fully solved

Since there are no right or wrong answers to complex problems, we must acknowledge that what we are trying to achieve is not solutions, but continuous improvement.

For those of us who work in the prison system, our goals are to improve the safety and security of prisons, protect the public from harm, reduce re-offending, and deliver swift access to justice. None of these are problems that will ever be ‘solved’ — they are not items to tick off a to-do list, and then move on. All the projects our teams work on, the services we design and deliver, the policy decisions we make — they’re all trying to move us as a society just a little bit closer to those goals.

During the first wave of COVID in early-2020, our teams were asked to implement on a wide scale the prison video-call service we had been testing in a few prisons. After understanding how the service could function, identifying what technologies existed, going through procurement exercises, and building out and testing the online and offline aspects of the service, we had to then tackle complicated technological and policy questions around cost and security. Now that we’ve fully rolled out the service to all 100+ prisons and ironed out many of the kinks, other questions will surely arise. How might we use the service to achieve wider goals around safety, building people’s skills, and helping secure accommodation before people are released from prison. As technology changes in the future, will our cost and security models need to change too?

Policy and service design questions will continue to arise, as long as the service exists and the policy objective (to connect people in prison with people in the community) persists. The service will never be ‘finished’. The policy objective will never be completely ‘achieved’.

And remember, all of this work is simply improving how people in prison connect with their loved ones, or access training or other support. It doesn’t ‘solve’ the larger problems of how to create safe and secure prisons, or reduce re-offending — it’s just a contributing factor. That wider work will also continue, forever. We need teams that are in it for the long haul — managing (or ‘stewarding’) systems to continuously perform more efficiently and achieve society’s goals.

Agile and systems thinking are not fads

The only way to achieve the goals we set for teams tackling complex problems is to develop a deep understanding of the issues, test improvement ideas, learn from those tests, and adapt our approaches — continuously.

And those processes must be done quickly, because if we wait months or years to see the impacts of our changes, it will be impossible to disentangle the impact of our changes from everything else that’s happened around them.

That is why policy and service design teams that see the whole system and work in agile ways to improve it — and organisations that adopt this agile mindset of continuously learning and adapting and improving, and design their org structure to enable that process — will be more successful than those that tend to see the world in terms of discrete problems to be solved.

Organisations that acknowledge the uncertainty they’re operating within and humbly work to make things better day-by-day, year-by-year, and decade-by-decade are the ones that will, over the long run, help us achieve the results we want to see in society.

Join our community

We use this blog to talk about the work of the multidisciplinary policy design community. We share stories about our work, the thinking behind it and what policymaking might look like in the future. If you would like to read more, then please sign-up for blog updates in the sidebar of this page. If you work for the UK's government, then find out how to get involved on our community page. If you don't work for the UK government, then join our AHRC Design and Policy Network.

3 comments

Comment by G posted on

Anything we build, a system, a building, a car, whatever it is is built on a foundation, and it is the foundation that causes every issue we face.

Read through the manaianway.com or karmiccredits.com to understand how it is possible to solve complex issues as these systems are holistic and symbiotic in thinking, as all things are connected.

There is only complexity when the thought solving the problem is not large enough.

Comment by Jeffrey Allen posted on

Yes... I think the extent of the interconnectedness of issues can be really daunting for a lot of policymakers. But as you say, there are methods to help them work through that complexity. The first step, I think, is to get policymakers and senior leaders to acknowledge that a new way of addressing problems is necessary. Then the methods come into play...

The Three Horizon model of viewing the world feels quite relevant here too (Horizon 1 = BAU / Horizon 2 = improving what exists / Horizon 3 = building a new future)... This explainer from Cassie Robinson makes me think about how policymakers could be working across all three of these horizons. And they can do that by not just asking 'what's troubling' (Horizon 1) and 'what's working' (Horizon 2), but by also asking 'what's hopeful' (Horizon 3), and finding ways to pursue all three of those paths.

https://cassierobinson.medium.com/funding-the-third-horizon-ef76a60be9bb

Comment by Willy Vandenbrande posted on

Thanks for an interesting article. I am familiar with the Cynefin model from David Snowden and with the probe, sense, respond logic for complex problems. In my view there are couple of obstacles to applying this in problems like "detention", "education", etc.

For one, in view of current legislation the window for probing is very narrow. You can almost only probe within a by law restricted area. Secondly, in a democracy, all involved parties must have a say. As a consequence it takes a long time before agreement can be reached on what probing to do and in what circumstances. Thirdly, many societal systems are slow by nature so before you can really sense the effect of your probing, it can take a long time. Political change during that time can kill interesting tests.

I fully agree with the article but want to warn that "agile" may sound as "quick" but that will definitely not always be the case, even without mentioning the forces that are against any change anyway.